So, there is yet another media article pondering whether Victoria’s lockdown is warranted… These articles invariably mention various countries, the level of restrictions, number of deaths and sometimes the current trajectory of cases. We’ve read it all before.

The latest article I read* notes that fewer than 900 Australians have died due to COVID, a small fraction of the approximate 160,000 Australians who die each year. The question posed, and answered by implication, is whether Victoria’s lockdown has saved lives or stifled them? But a proper counterfactual is missing – how many lives has lockdown saved?

Sweden provides a useful point of reference, because rather than having very strict mandates from government, it relies more on individual actions and choices of people. If Australia had the same per-capita death rate as Sweden, approximately 15,000 Australians would have died. We’d also have a similar number of deaths if Australia’s per-capita death rate had been the same as in Italy, Spain, UK, or USA (remembering these other countries have had various lockdowns too). So restrictions in Australia have seemingly been effective, and compared to some other countries, might have saved at least 14,000 lives so far.

And let’s emphasise so far. The COVID pandemic has a fair way to run – likely well into 2021 if effective vaccines are not available within the next few months. And we should remember that the number of deaths is only one measure of the impacts: long-term health effects are also prominent.

The other counterfactual to consider is how much better our lives would be with laxer restrictions. Sitting in Melbourne, I have not left my suburb for a couple of months, I’ve been working from home for six months, and I’m unlikely to return to my office until sometime next year. And I could live without any more zoom/teams/meet/webex meetings for a while**. I would love to have fewer restrictions. But would I love the increase in cases that would arise if restrictions were lifted?

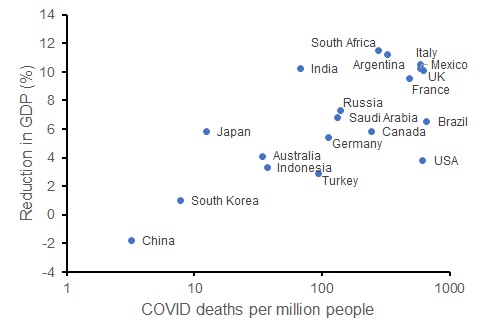

While I recognise that the social and economic impacts of the pandemic are multi-faceted, change in GDP for each country provides one measure of this. Let’s consider the G20 countries. We can compare the current per-capita death rate from COVID to the OECD’s forecast reduction in GDP for each country in 2020. That relationship indicates (somewhat crudely) what might have happened to Australia’s economy in the presence of more deaths (which would occur with laxer restrictions).

Contrary to the view that saving lives via restrictions reduces economic outcomes, COVID death rates are positively correlated with economic harm. The G20 countries with lower COVID death rates have experienced a smaller reduction in GDP than those countries with more deaths. While this is merely correlative, these data show that had we implemented softer restrictions, Australia could have had worse economic outcomes – the issue is the degree to which the disease (rather than the restrictions) harms the economy.

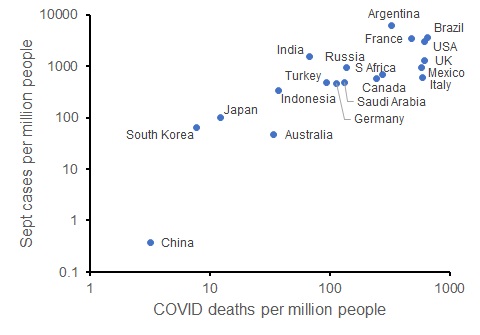

We can also look at the trajectory of the disease in each of these countries: the number of new cases per capita so far in September (up to 25 Sept) also correlates with the current COVID death rate. So those countries that have limited COVID deaths are on track to have fewer new COVID cases (and likely fewer deaths in the future, and potentially better economic conditions).

The COVID pandemic still has months to run; in the absence of a vaccine, it will be many months. But so far, countries have had more than 100-fold differences in per-capita deaths from the disease and quite different economic impacts. All countries have imposed various restrictions. The comparatively onerous restrictions in Australia have likely saved up to 14,000 lives when compared to the worst-hit G20 countries. And the OECD forecasts that the economic impact on GDP will comparable or better in Australia than most other G20 countries.

Clearly, Australia’s economic and health outcomes would have been better without Victoria’s spike in cases that originated from a breach of hotel quarantine. However, once the breach had occurred and cases were increasing rapidly from June, Victoria’s subsequent lockdown reduced the number of deaths and long-term illnesses that would have otherwise occurred.

Consider Arizona, a US state with a similar population size to Victoria. Arizona had a large spike in cases that peaked in early July at around 4000 cases per day, forcing the implementation of more restrictions. With about 10 times as many infections as Victoria, Arizona has also experienced about 10 times as many COVID deaths.

Now with around 500 cases per day in Arizona (close to Victoria’s peak in early August), they have recorded infections in about 3% of the population compared to Victoria’s 0.3%. With the vast majority of the both populations yet to be infected, the number of cases and deaths could rise substantially in both states in the absence of control measures. But cases in Arizona remain high – much higher than in Victoria, and the health (and economic) prospects seem much worse in Arizona than Victoria.

We are seeing alarming increases in new cases across much of Europe since the start of July, an indication of what can happen if the disease is not controlled: exponential growth. The feature of exponential growth is that cases accelerate rapidly from seemingly low levels. These other locations provide the counterfactual of what happens to the number of cases if COVID is not controlled. Counterfactuals for the economic impacts suggest that controlling the disease can also lead to better economic impacts, something that a range of economists predicted at the start of the epidemic.

The next time someone muses about whether controlling COVID is worse than the disease, I sincerely hope that they make a decent fist of trying to answer that question. Because when I look at the evidence, the answer seems to be a resounding “no”.

————————————————-

* I am not going to link to the article – it really seems to be click bait.

** I have about 20 meetings already in the calendar for next week, which could be worse now that the bulk of my teaching has just finished for the year. And while I might moan, virtual meetings are so much better than no interactions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.